Bauhaus

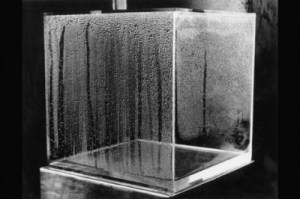

Labour forms a metabolic link between humankind and nature. There is our own labour – a labouring through the world that constitutes our everyday – and then there is a kind of labour that we read onto things. It is not very often that we are confronted by a stillness that cannot be overwritten by movement, or process. Function-less form makes no sense to the labouring eye. Some artists have deliberately materialized this vertiginous impulse. Robert Morris’ Box With the Sound of Its Own Making (1961), in which he installed a feedback-loop recording of the labour of constructing the box, within the form itself. Here, form is literalized as a carrier of functions. Some objects, like tools and instruments, give off a greater sense of immediate use, while ‘Do not touch’ artworks fall in at the other end of the scale. Paradoxically, traditional aesthetics has supplemented this distancing from touch by installing our metabolic reflexes within the act of looking itself, whereby mere witnessing is transformed into the act of beholding. This is a peculiarity of aesthetics that borders on a kind of fetishism (insofar as one sensuous domain is recruited to compensate for another’s withdrawal).

Bauhaus sought to rectify this fetishism by shifting the burden of representation back on to the crafts and practices that go in to production. This Modernist project realized what Douglas Crimp would later go on to theorize as ‘cultural practice’. (Interestingly, this shift occurred soon after Wölfflin’s Principles was published. Wölfflin pushed the fetishism of aesthetics to its formalist limit, by investing vision with the sculptural qualities of material praxis (i.e. he posited a vision that was able to penetrate and remodel physical attributes of the object).) Bauhaus failed because, although representation had been shifted on to the ethics of practice – i.e. the School – its utilitarianism was still ultimately subject to the production and display of objects (cf. the recent Barbican exhibition). Attempts to erase the object, to present labour in-itself, have multiplied in every direction since the day Bauhaus lay washed up on the shores of America. Most recently, Nicolas Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics and its theorization of participatory art projects presents a move to categorically replace aesthetics with ethics, as the correct backing epistemology for the production/reception of artworks. But even so, the same problem that arose with the Bauhaus remains: how to represent the event after the event and what to do with the audience. Instead, I want to chart and imagine instances where we, as spectators, have moved in the opposite direction. A situation where art objects become the raw materials to kinds of representative practices that take place beyond the gallery space. I want to look at the production of lifestyles as an unintended offshoot to the determinate blurring of the borderland between art and life. We no longer labour to survive; today we labour to look good. I want to locate instances that realize Bourdieu’s attack on Kantian aesthetics, instances where subjects maximize on their social capital. I do not intend to valorise the production of lifestyles from artworks, but instead the hope is that, by recognizing and pushing its methods and labour, we might be in a position to question the validity of practices that seek to redress the ‘fetishism’ of aesthetics with a well-meaning ethical commitment that – as I claim – backfires. By surpassing this commitment, I hope to draw the parameters of renewed possibilities for aesthetics today.